Conspiracy theories are not new to American politics. From 18th century anxieties about Freemasons to theories on a modern day Illuminati,, such beliefs have always found fertile ground in times of upheaval. Today, with declining trust in institutions and fragmented media, conspiracy theories remain widespread. A new Change Research survey of 1,590 voters, conducted in late August 2025, highlights the scope and impact of this phenomenon on public life and politics.

Conspiratorial Thinking in Historical Context

To set the stage, it is useful to understand how today’s conspiratorial beliefs echo earlier eras. Scholars have described the “paranoid style” in American politics as a recurring pattern—one marked by apocalyptic visions of good versus evil, suspicions of hidden enemies, and elaborate explanations for political events.

By conspiracy theory, for this research we mean a belief that some secret but influential individual or organization is responsible for an event or phenomenon. Importantly, we make no judgment here about whether such theories are true or false; our focus is on how widely they are held and what they reveal about public trust.

- Public trust in government has steadily declined in the 21st century.

- After a brief post-9/11 spike, confidence in Washington’s ability to handle domestic and international problems has fallen sharply.

- In 2025, only 37% of voters trust the federal government on domestic issues, while trust in its handling of international affairs shows similar weakness.

This long-term decline in institutional trust provides a backdrop against which conspiracy theories can flourish.

Mapping the Electorate’s Belief Profiles

Not all voters engage with conspiracies in the same way. The survey identifies three broad groups that reflect distinct attitudes toward conspiracy theories.

- Deep Conspiracy Believers (36%)

This group holds the strongest conspiratorial beliefs across nearly every dimension. They express extremely low trust in all institutions, including scientists, and often feel personally targeted by hidden forces. As a result, they are the most alienated and suspicious segment of the electorate. - Selective Believers (36%)

These voters maintain high levels of conspiracy belief but show a distinct pattern of retaining trust in scientists and academics. While they distrust government and media and assume politicians often hide information, they continue to respect some expert knowledge. They represent a group of “educated skeptics” who straddle suspicion and respect for expertise. - Moderate Skeptics (29%)

Moderate skeptics show only limited belief in conspiracies compared to the other groups. They express the highest overall trust in government and media and are the most persuadable segment of the electorate. Open to multiple sources of information, they are closest to what is broadly thought of as mainstream public opinion.

Perceptions of Secrecy and Hidden Agendas

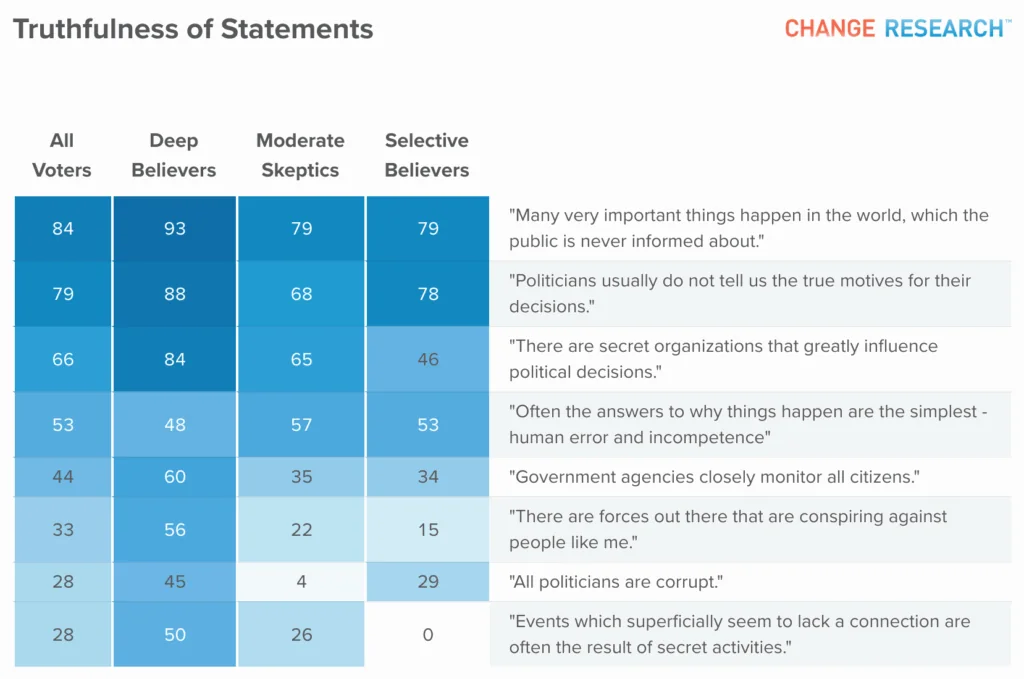

A consistent theme across all three groups is the belief that much is hidden from the public. These sentiments are not confined to the most conspiratorial segments but run broadly through the electorate. In fact, more than four in five voters say many very important things happen in the world without the public ever being informed. Nearly eight in ten agree that politicians usually conceal their true motives, while two-thirds suspect that powerful people work in secret to shape major political and economic events. Even when accounts of an event conflict, large numbers assume deception: over four in ten think such contradictions almost always signal a cover‑up, and nearly as many believe it happens at least some of the time.

Trust in Institutions and Sources of Information

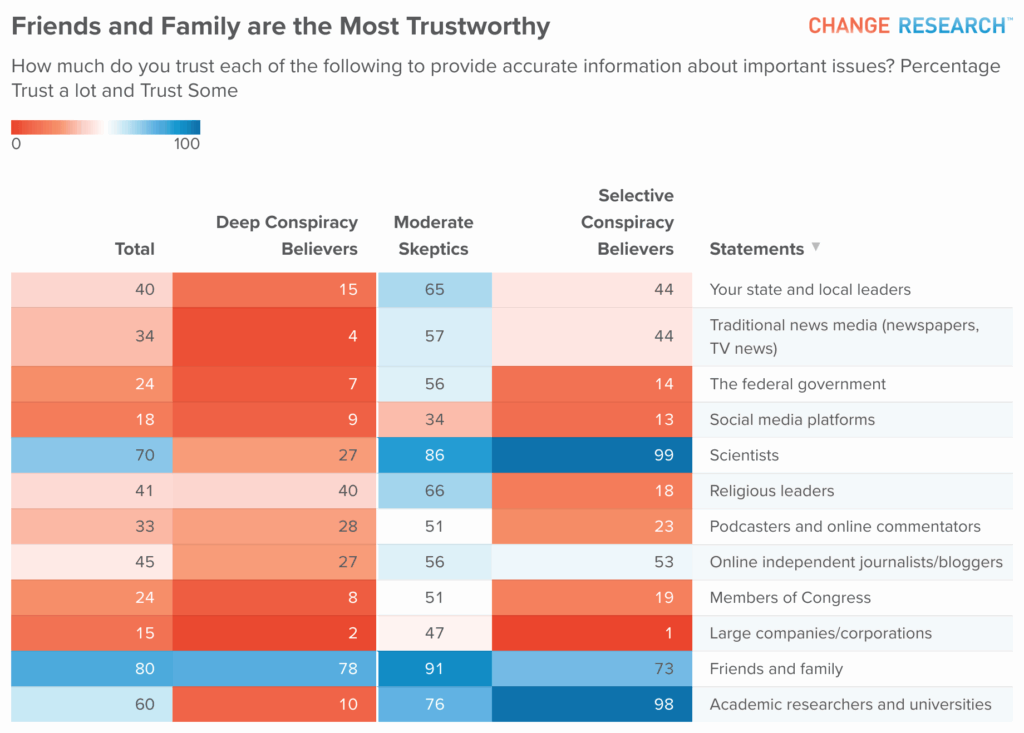

When it comes to who Americans rely on, trust follows a clear hierarchy. Personal connections and scientific expertise fare best, while political and corporate institutions are met with deep skepticism.

- Most Trusted: Americans show the greatest trust in people close to them and in science. Friends and family are considered the most reliable source of information, followed by scientists and, to a lesser extent, academic researchers.

- Least Trusted: By contrast, trust plummets when it comes to larger institutions. Corporations, social media platforms, Congress, and the federal government all receive deeply negative ratings. Even traditional media outlets register more distrust than confidence among the public.

This divergence suggests that while people turn to personal networks and scientific authority, they remain wary of institutional and political actors.

Which Conspiracies Resonate Most

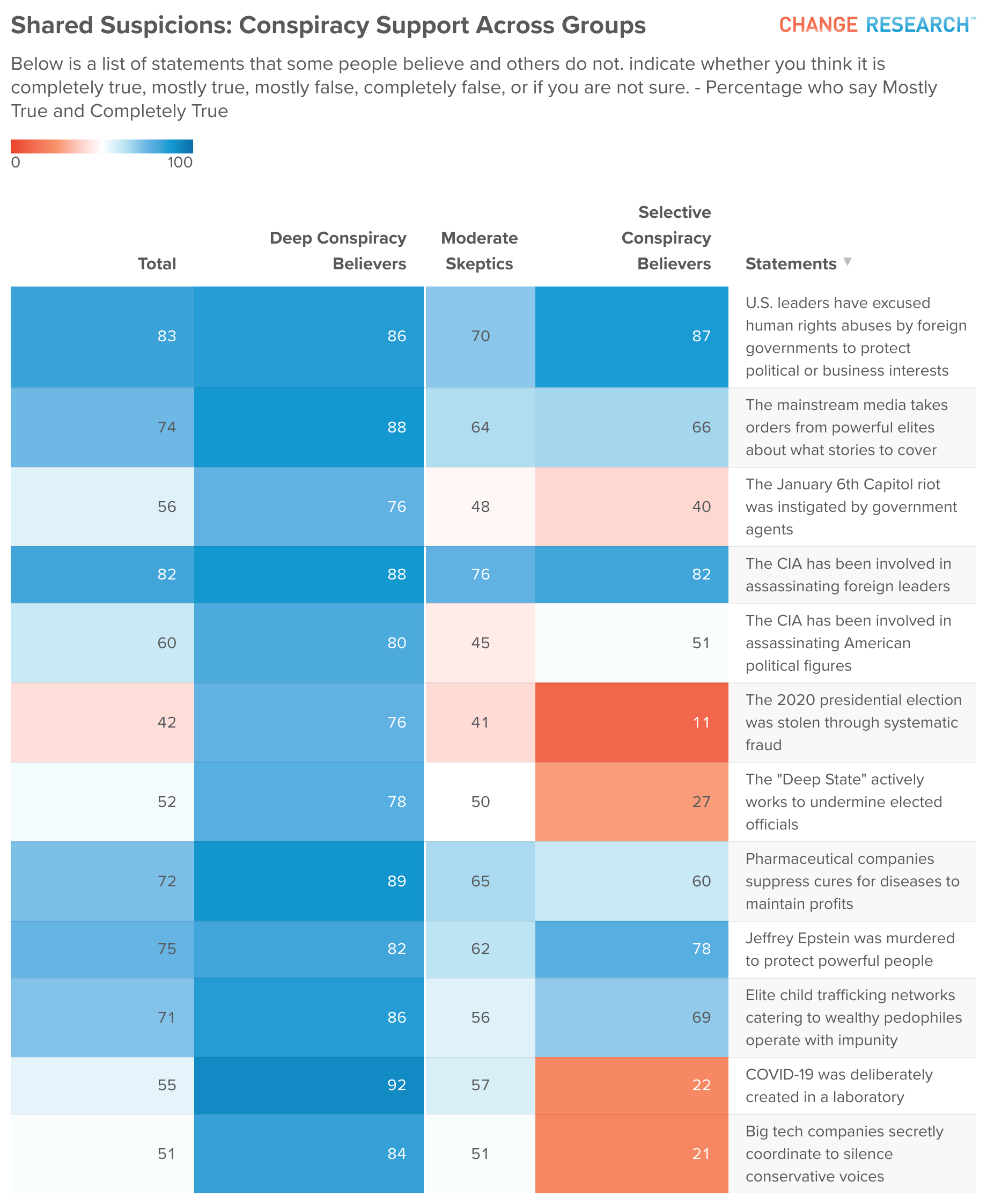

When tested on specific narratives, Americans revealed a mix of broadly accepted and widely rejected beliefs.

- Beliefs considered more likely true than false: Large numbers of Americans say they believe powerful actors have hidden motives. For example, 79% think U.S. leaders excuse human rights abuses abroad for business interests, 70% believe the CIA has been involved in assassinating foreign leaders, and 64% are convinced the mainstream media conceals damaging stories about elites.

- Beliefs considered more likely false than true: At the same time, voters reject other claims decisively. One in ten support the idea that the Earth is flat, about one-thirds support the notion that the moon landing was faked, and 38% say mass shootings have been staged to promote gun control.

Still, some contested claims divide opinion. A portion of selective believers, for instance, argue that climate change is exaggerated or manipulated, underscoring the polarized landscape of trust in science.

High-Profile Examples: UFOs and Epstein

Certain issues generate particularly strong reactions, drawing wide attention and speculation.

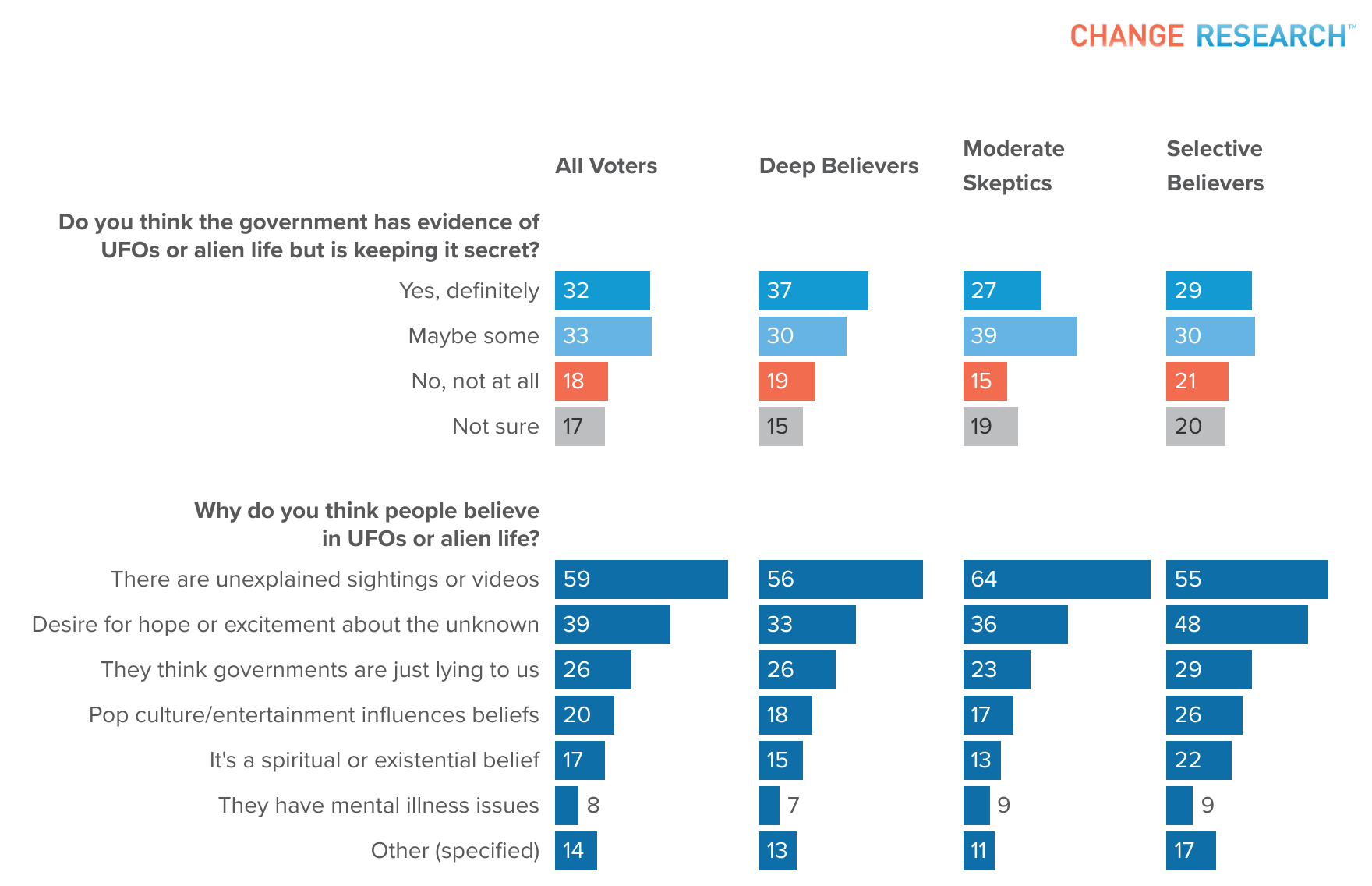

- UFOs and Alien Life: Two-thirds of voters say they believe the government may be hiding evidence of extraterrestrial life. About one-third are certain of it—32% say “definitely”—while another 33% are less sure but say “maybe.” The most common reason given for these beliefs is the prevalence of unexplained sightings and videos, which 59% cite as evidence.

- Jeffrey Epstein: The case of Jeffrey Epstein remains one of the most prominent modern examples of public distrust. Nearly two-thirds of voters, 63%, believe he was murdered rather than hanging himself with a bedsheet in his jail cell. By contrast, only 14% accept the official ruling of suicide, while the remainder remain uncertain about what really happened.

These examples highlight how official accounts often fail to overcome public skepticism, especially when scandals or secrecy have already shaped perceptions.

Political Consequences

The survey makes clear that conspiracy beliefs influence how voters judge candidates and their messages. Outsider status, anti-establishment rhetoric, and promises of exposure resonate strongly with large majorities.

- 73% prefer candidates who are outsiders to the political establishment.

- 85% say it is important that candidates share their views on who really controls government.

- 73% would be more motivated to support a candidate who promises to “investigate and expose corruption.”

When evaluating government failures, voters are most persuaded by explanations pointing to corruption or capture by powerful interests, rather than lack of funding. For example, 62% find compelling the argument that agencies have been “captured by interests that don’t prioritize public safety.”

A Challenge for Governance

The persistence of conspiracy thinking poses a difficult paradox. Politicians can gain support by tapping into distrust, but this same rhetoric erodes the very institutions needed to govern effectively. The study underscores that while conspiratorial thinking has always been part of America’s political fabric, today’s combination of low trust and fast-moving digital communication gives such narratives new reach and influence.