So much political commentary tries to make simple things look complicated to explain past events and predict the future. After an election, we come up with explanations of why events happened – Critical Race Theory! Respect Parents! – backed up with little to no data other than exit polls that might be right and might not be. Months later, we get simpler tools – the voter file update, which tells us who voted and didn’t vote. While this doesn’t illustrate why people made their decisions, it tells us who didn’t vote and who did. Democrats massively underperformed in the gubernatorial elections in New Jersey and Virginia last year compared to 2017 and the 2020 presidential vote. Diving deeper into who comprises the electorate can give us clues to how Democrats need to adjust strategies for the 36 gubernatorial contests held this fall. To summarize:

- 2022 will break records for voter participation. In Virginia, 37% of 2021 voters did not vote in the 2017 gubernatorial election, and 40.6% of 2021 voters in New Jersey did not vote in 2017. Many are new registrants – 11.8% of 2021 voters in Virginia and 9.6% in New Jersey registered since the 2017 election. We should expect a similarly high turnout in gubernatorial elections in 2022 with a substantially different electorate from 2018.

- A substantial share of new voters will be people who voted in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections but not in the previous gubernatorial election. This group was substantially more Republican than the electorate based on the Change Research 2020 voice choice model created by Change Research’s Data Science team of Nina Wornhoff and Julia Slisz. Moreover, those who voted in 2017 but not in 2021 were significantly more Democratic than the new voters entering it in both states.

- A higher share of Trump voters participated in these contests than in 2017 and 2020, producing a more Republican electorate at the outset in Virginia and New Jersey. This should be baked into our turnout and persuasion plans this year.

- Democrats left too many votes on the table. There were 1,123,366 likely Biden voters who did not vote in either the 2017 or 2021 gubernatorial contests in New Jersey. There were 631,782 in Virginia. Democratic campaigns did not reach them in a way that compelled them to vote. We have to understand these voters more deeply this year and try different ways of outreach and paid communications.

- Democratic candidates can’t assume Biden’s level of support. In both New Jersey and Virginia, more votes switched from Biden to the Republican in 2021 than the other way. Terry McAuliffe lost the election because of Biden-Glenn Youngkin voters. More nuanced messages will be required in Governor’s races than simply tying the nominee to Donald Trump’s excesses, even in states Biden won. Terry McAuliffe also lost rural southwest Virginia so much that he offset all his gains in Northern Virginia. Democrats can lose even more of rural America than they have already.

New Jersey & Virginia: Historical Trends

Held the year after the presidential election, Virginia and New Jersey have accurately reflected the national mood a year into a new administration in DC and predicted the outcomes in many other states the following year.

- In 1993, Republican George Allen handily defeated Democrat Mary Sue Terry by 17.6 points in Virginia while Republican Christie Todd Whitman ousted Democratic Governor Jim Florio in New Jersey. Republicans went on to flip 12 governor seats in 1994.

- In 2001, just weeks after the terrorist attacks on September 11th, Democrats replaced Republicans in Virginia and New Jersey. Mark Warner won by 5.2 points in Virginia and Jim McGreevey won by 14.7 points in New Jersey. Democrats went on to flip Arizona, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Wisconsin, and Wyoming the following year despite losing ground in both the U.S. House and Senate.

- In 2009, despite Barack Obama’s historic victory a year earlier, including the first Democratic win in a presidential election in Virginia since 1964, Democrats lost in both states. Republican Bob McDonnell trounced Democrat Creigh Deeds by 17.3 points in Virginia and Republican Chris Christie smothered Democratic Governor Jon Corzine by 3.6 points. Republicans went on to seize 11 gubernatorial seats the following year.

- In 2017, Democrats handily won both states (Virginia by 8.9 points, New Jersey by 14.1 points) and went on to take back Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, and Wisconsin the following year.

Given this history, it was reasonable to expect that Republicans would win both states despite Joe Biden’s double-digit victories in 2020 (Virginia by 10.1 points and New Jersey by 15.9 points). Republican Glenn Youngkin won Virginia by two points while Democratic Governor Phil Murphy held his seat in New Jersey by 3.2 points. Republicans expanded the electorate, turned out their voters at a higher rate than Democrats, and flipped enough Biden voters to win Virginia and come close in New Jersey. Unless Democrats come up with strategies to blunt this impact and turn out presidential year only voters at equal rates, or higher, than Republicans, a similar fate awaits Democrats nationally in 2022.

What Happened in 2021

No two elections are the same. New voters come into the electorate while others leave it. Voter participation surged to historic levels in both states in 2021. Participation increased from 2017 by over 675K votes in Virginia and 467K in New Jersey. The Democratic nominee in Virginia, Terry McAuliffe faced an electorate that contained more voters who didn’t vote in 2013 (1,656,715), the year he won the governorship than those who did (1,598,471). This differed substantially from 1993 and 2009 when Democrats lost both states, but the total number of voters was similar to the previous election for governor.

This increase in turnout allowed the Republicans to surge even though McAuliffe got more votes than Ralph Northam in 2017 and Murphy got more votes than he did four years earlier. Republicans Glenn Youngkin in Virginia and Jack Ciattarelli in New Jersey improved their party’s 2017 nominee’s vote share more substantially.

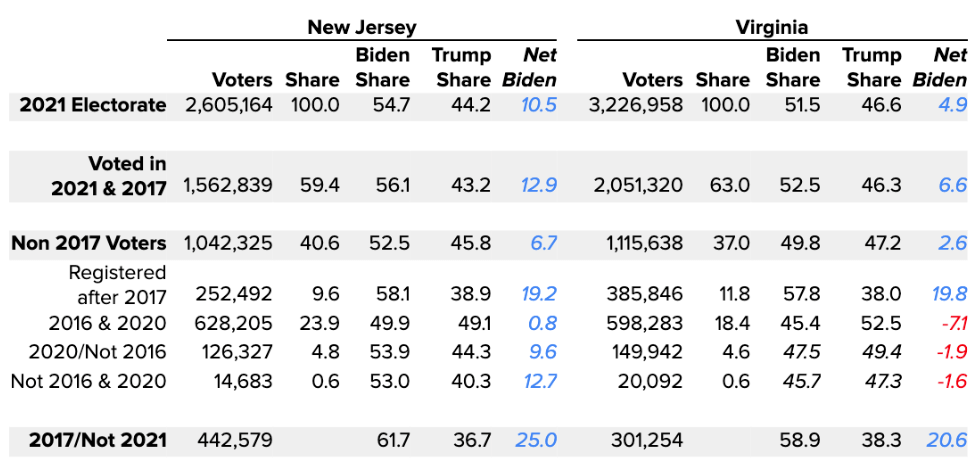

After the 2020 election, the data science team at Change Research created a vote choice history model to determine the likelihood of each voter in America voting for Joe Biden, Donald Trump, or a third party. In applying this model to voters in New Jersey and Virginia, we can more precisely measure the impact of the partisan composition of this changed electorate on the final result. In New Jersey, we estimate the 2021 electorate was 54.7% Biden voters and 44.2% Trump voters, a 10.5 margin. This represents a drop of 5.4 points from Biden’s 2020 margin in the state. In Virginia, there were more Biden than Trump voters in 2021. Biden would have won the 2021 electorate by 4.9 points instead of the 10.1 points he won a year earlier. The table below shows the more detailed composition of the electorate based on other elections people voted in.

Overall, 40.6% of the electorate in New Jersey and 37.0% in Virginia didn’t vote in 2017. More of these new voters voted for Biden than Trump in 2020. However, the overall Democratic margin slips because the departing voters, those who voted in 2017 but not in 2021, were substantially more pro-Biden.

In both states, Biden did significantly better with those who voted in among those who voted in both gubernatorial elections as opposed to those who voted only in 2021. Republicans gained the most ground with those who voted in 2020 and 2016, but not 2017. This group represented a substantial share of the electorate in both states (23.9% in New Jersey and 18.4% in Virginia). They split evenly between Trump and Biden voters in New Jersey and more towards Trump in Virginia. This suggests voters who voted in the last two presidential year elections, but not 2018, will provide the margin of victory for the Republicans who win in 2022.

Democrats have the greatest opportunity next year with voters who have registered since the 2017 gubernatorial election. They comprised 9.6% of the electorate in New Jersey and 11.8% in Virginia. They went much more heavily towards Biden than Trump than the electorate overall.

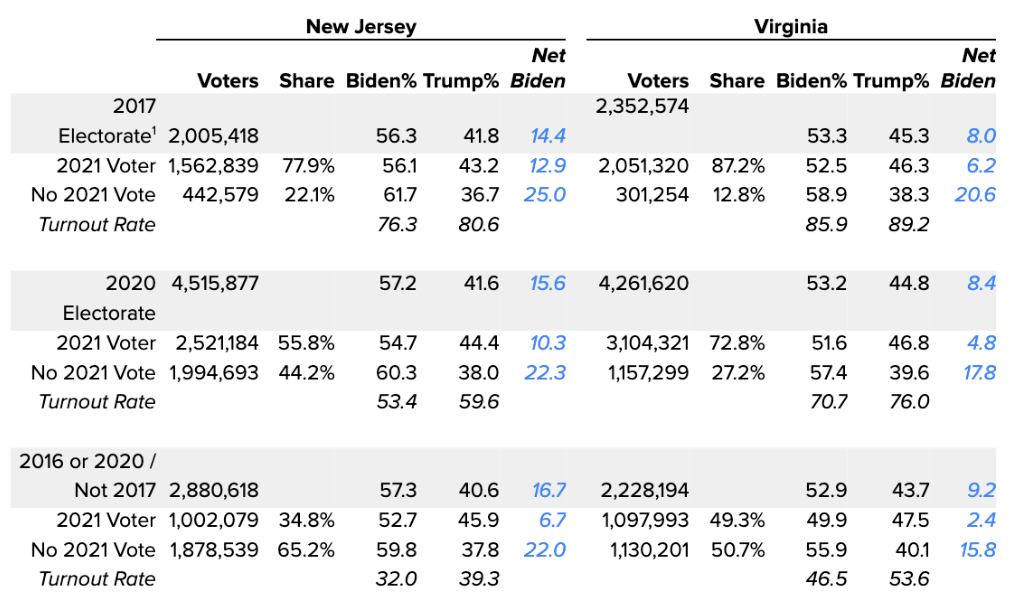

However, in New Jersey and Virginia Trump voters turned out at higher rates than Biden voters. Among 2020 voters, those who voted in 2021 were substantially less likely to have voted for Biden over Trump than those who sat 2021 out. Gubernatorial contests are often determined by which party can turn out those who have voted in recent presidential elections but not the most recent midterm. In New Jersey, 1,123,366 of these presidential-year-only voters were likely Biden supporters but didn’t vote in 2021 despite millions of dollars spent to persuade and turn them out. In Virginia, 631,782 of likely Biden voters who voted in 2020 failed to show up compared to 453,211 presidential year-only likely Trump voters. This 178,572 difference is nearly three times as high as the final margin between McAuliffe and Youngkin (63,688).

The raw vote counts for the 2017 and 2020 electorate are based on the number of people currently on the voter file in those states, not the total who voted in that election at the time.

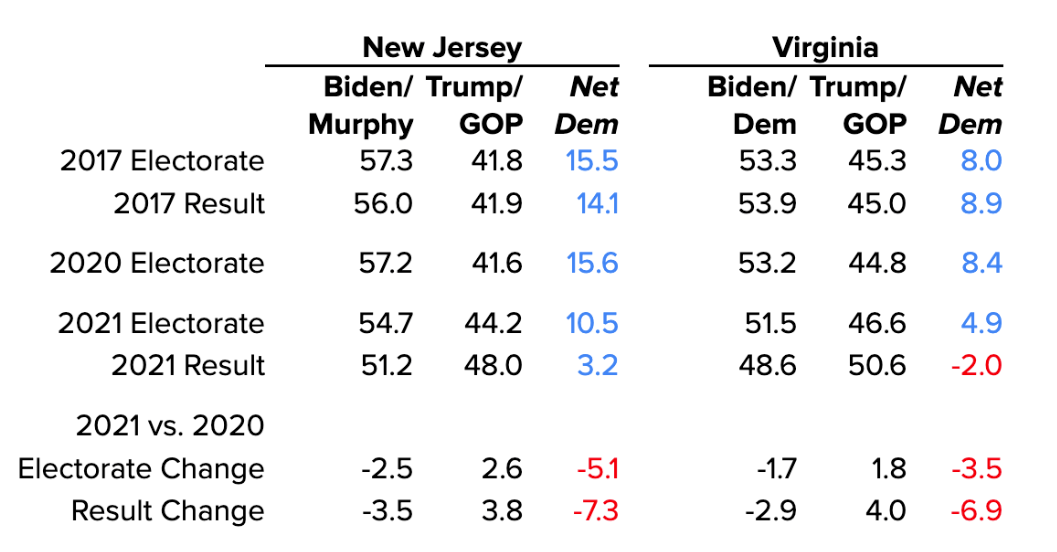

Beyond the changing composition of the electorate, voters also switched parties from their 2020 choice in the presidential election to their selection for Governor in 2021. In 2017, we estimate the electorate in New Jersey to have been Biden +15.5, with Murphy winning by 14.1 points. The 2017 electorate more closely mirrored the 2020 electorate than 2021. Biden won the state by 15.9 points in 2020. Phil Murphy won by just 3.2 points, representing a -12.7 point shift in Democratic margin in a year. Our model suggests 5.1 points of that shift came from partisan changes in the electorate and 7.3 points from vote switching, mostly driven by voters switching from Biden to Ciattarelli.

Vote switching played a relatively greater role in Virginia. In 2017, the electorate also mirrored the preference of voters who would show up in 2020. Our data shows that the 2017 electorate favored Biden by 8 points, with Ralph Northam winning by 8.9. Biden won the state by 10.1 points, the widest margin for a Democrat since FDR won his fourth contest by 25 points in 1944. However, Terry McAuliffe lost by 2 points a year later. This represents a -12.1 point shift in the Democratic margin. Our model suggests only 3.5 points in the shift came from changes in the electorate. That shift alone would have still left a six-point Democratic advantage, comparable to the 6.3 point margin Barack Obama won the state in 2008. However, we estimate that the vote switching from Biden to Youngkin moved the margin by 6.9 points, ultimately costing McAuliffe his comeback.

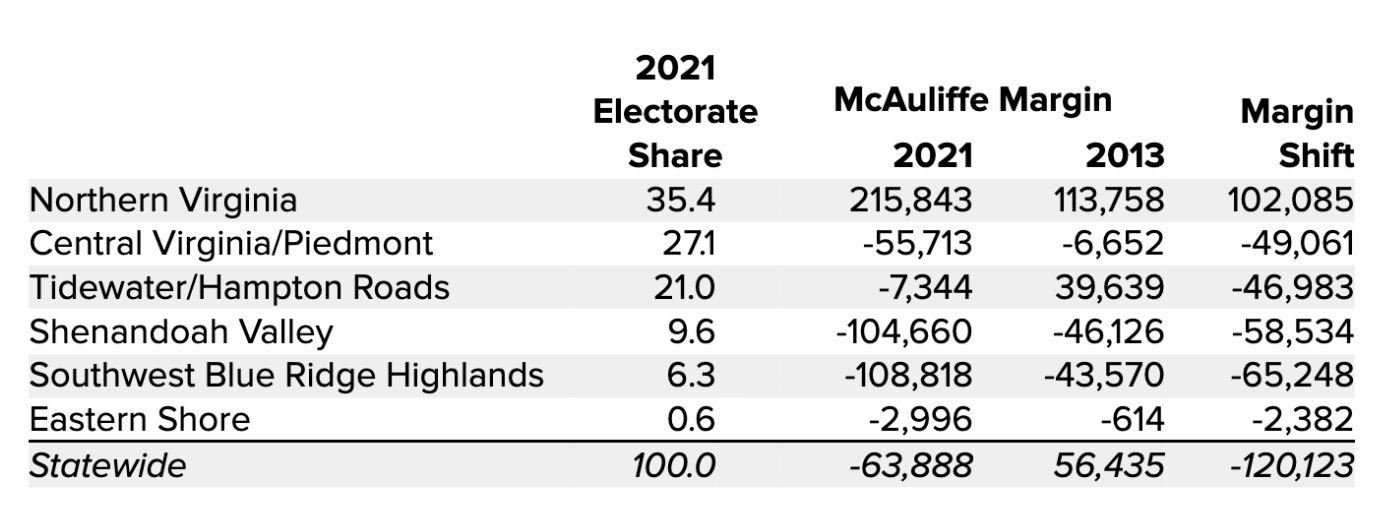

While we can isolate effects between changes in the electorate and change in the vote, the voter file can’t tell us why people changed their vote. We do know that pre-election surveys showed McAuliffe as more disliked (44% favorable-43% unfavorable in a Roanoke College survey released on October 30th) than Youngkin (45% favorable-37% unfavorable). Despite that, compared to McAuliffe’s successful campaign for Governor in 2013, he increased his margin in Northern Virginia by more than enough to offset losses in the Richmond area and Tidewater/Hampton Roads. However, Youngkin’s increases over the 2013 nominee Ken Cuccinelli’s margins in the Shenandoah Valley and Southwest Virginia regions were enough to wipe out McAuliffe’s winning 2013 margin. This shows that Republicans have yet to maximize their advantage in rural America and have even more room to grow.

What This Means for 2022

Looking under the hood at these somber results shows that Democrats can prevail in 2022. We know who our voters are and where they live. We know they voted for Joe Biden and are open to voting for other Democratic candidates. Democrats will face a substantially different electorate in 2022 than in 2018. That was foreshadowed in New Jersey and Virginia the year before. Based on 2017 to 2018 and 2021 to 2022, there will be a substantially higher turnout in 2022 than in any previous gubernatorial election. That will be driven largely by Republican voters who voted in 2016 and 2020 but skipped 2018. To match that, Democrats will have to finely target Biden voters who didn’t vote in 2018 and develop unique messages to address their concerns.

What Democrats did in 2021 did not work well enough to bring Democratic voters out in the numbers needed to offset Republican tactics and turnout. If Democrats run the same campaigns the same way this year as they ran them last year, we will lose across the country. Democratic incumbents were elected by smaller margins in 2018 than Ralph Northam and Phil Murphy, and Biden came much closer to Trump in states like Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and other states that we have to defend in 2022 than he did in New Jersey and Virginia.

Losing swing state gubernatorial seats will be the gateway to Donald Trump’s comeback in 2024 with Republican MAGA governors and legislatures poised to take the vote away from their citizens. But if campaigns can learn the lessons of 2021 now, there’s an opportunity to effectively counteract these trends. We need to all hands on deck to expand the Democratic electorate and promote the success of our Governors to bring in the voters who stayed home in 2021.

—-

Report by: Stephen Clermont, Director of Polling

Data Analysis by: Julia Slisz & Nina Wornhoff, Data Scientists