Conspiracy theories are often treated as fringe beliefs, confined to the political margins. Yet new data from Change Research shows they are possibly more widespread, and in some cases majority-held views among American voters. These findings point to a deeper, systemic issue: a decrease of trust in the institutions that shape public life. By conspiracy theory, we mean a belief that some secret but influential individual or organization is responsible for an event or phenomenon. Importantly, we make no judgment here about whether such theories are true or false; our focus is on how widely they are held and what they reveal about public trust.

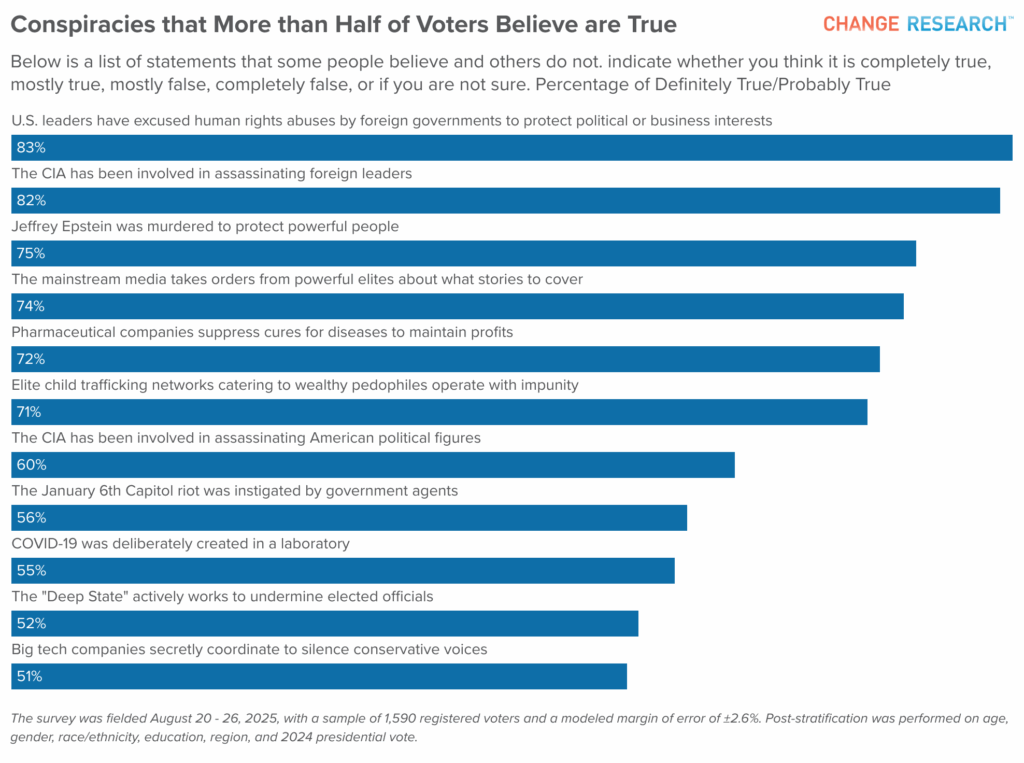

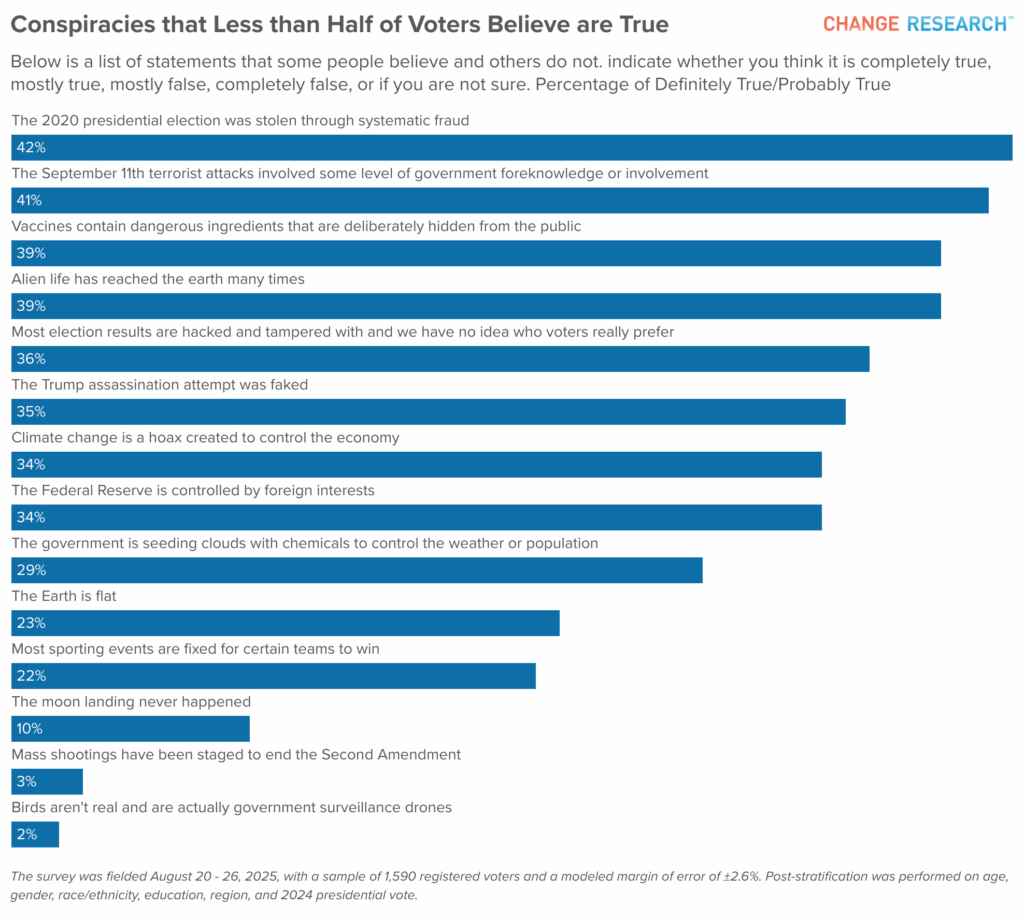

The survey was fielded August 20–26, 2025, with a sample of 1,590 registered voters and a modeled margin of error of ±2.6%. Post-stratification was performed on age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, region, and 2024 presidential vote to ensure representativeness. The results of this collapse are those who said Definitely true and Probably true when asked about a list of conspiracies (Question Text: Below is a list of statements that some people believe and others do not. indicate whether you think it is completely true, mostly true, mostly false, completely false, or if you are not sure.)

The results reveal two clear patterns. First, when conspiracy theories align with existing institutional mistrust—whether toward government, the media, corporations, or technology—belief soars, often above 50% of voters. Second, theories that fall outside that framework, such as flat earth claims or staged moon landings, remain minority positions, though still supported by sizable groups.

Majority-Supported Conspiracies: Institutional Distrust

The Change Research survey shows that belief in conspiracy theories is not confined to the political fringes—a majority of U.S. voters believe some truth to at least one of common claims. Looking at the conspiracies most widely believed by voters shows that these narratives resonate most strongly when they tap into a deep mistrust of institutions. The largest share of voters (83%) say U.S. leaders excuse human rights abuses abroad to protect political or business interests, and nearly as many (82%) believe the CIA has assassinated foreign leaders. Majorities also embrace theories about elites manipulating events closer to home: 75% believe Jeffrey Epstein was murdered to protect powerful people, 74% say the mainstream media takes orders from elites on what to cover, and 72% believe pharmaceutical companies suppress cures to maintain profits. Even highly charged claims—like 71% saying elite child trafficking networks operate with impunity or 60% believing the CIA has assassinated American political figures—are supported by large swaths of the electorate.

Recent events also fall under this pattern of mistrust. 56% of voters believe COVID-19 was deliberately created in a lab, 55% think the so-called “Deep State” works to undermine elected officials, and 52% believe big tech companies secretly coordinate to silence conservative voices. Even the January 6th attack is widely interpreted through this lens, with 60% believing government agents instigated the riot. Across these narratives, the common denominator is suspicion that institutions—government, media, business, or technology—act secretly against the public interest.

Minority-Supported Conspiracies: Fringe and Far-Fetched

By contrast, the second chart shows theories that fail to gain majority traction, either because they are more extreme, more easily disproven, or less tied to mainstream institutional critique. Still, large minorities buy in: 42% say the 2020 election was stolen through fraud, and 41% believe the government had foreknowledge of the 9/11 attacks. Roughly four in ten also think vaccines contain hidden dangerous ingredients (39%) or that alien life has reached Earth many times (39%). About a third of voters believe that most election results are hacked (36%), that the Trump assassination attempt was faked (35%), or that climate change is a hoax created to control the economy (34%).

Further down the list, support drops sharply. 29% believe the government is seeding clouds with chemicals, 23% say the Earth is flat, and 22% think the moon landing never happened. Some of the most fringe claims—mass shootings are staged (10%) or birds are government surveillance drones (2%)—garner almost no support. These beliefs highlight the boundary where conspiracy thinking moves from mainstream skepticism into more marginal or fantastical territory.

Gender, Generational, and Educational Divides

While conspiracy belief is widespread, the differences across gender are relatively modest. Men are somewhat more likely to endorse foreign policy and intelligence conspiracies—for example, 88% of men vs. 76% of women say the CIA has assassinated foreign leaders. Women, meanwhile, are only slightly more inclined to believe in pharmaceutical suppression, with 72% vs. 70% of men saying cures are hidden for profit. On Epstein’s death and media manipulation, the gap all but disappears, with both groups in the high 70s to low 80s. Overall, these small differences show that institutional mistrust runs deep across both men and women, with belief levels largely aligned.

Generational differences exist, but the gaps are not especially large. Gen Z tends to be at the high end of belief across most conspiracies—for instance, 81% say U.S. leaders excuse human rights abuses and 86% say the CIA has assassinated foreign leaders, compared to 81% and 80% of Boomers respectively. On Epstein’s death, belief was similarly widespread, with 79% of Gen Z and 71% of Boomers agreeing. In most cases, younger voters are slightly more likely to embrace these narratives, but the pattern is one of consistently high belief across all generations, with Gen Z generally topping the list.

Education also plays a role. Non-college-educated voters are more likely to believe in media and pharmaceutical conspiracies—78% vs. 67% of college voters think the media takes orders from elites, and 79% vs. 60% believe cures are suppressed. On foreign policy claims, however, the divide is narrower: belief in CIA assassinations and leaders excusing human rights abuses is roughly equal across education levels. This suggests that while mistrust cuts across class lines, its expression differs, with non-college voters channeling more suspicion into narratives about media bias and corporate malfeasance.

The Big Picture

When placed side by side, the two charts illustrate a potential dividing line between mainstream and fringe conspiracy beliefs. The claims with majority support are not random—most seem to align with institutional distrust: that government assassins operate in secret, media stories are dictated from above, pharmaceutical companies suppress cures, tech platforms coordinate censorship, and national security agencies engineer political crises. Even newer flashpoints like COVID-19 and January 6th are absorbed into this framework of mistrust.

One way to interpret even minority-endorsed conspiracy theories is as a form of repudiation. Flat Earth beliefs can be seen as rejecting the authority of science, claims that the moon landing was staged as rejecting the authority of the U.S. government, and fears about vaccines as rejecting the authority of both science and business. But these views garner much less support than other conspiracies, suggesting that while skepticism runs deep, there are limits to how far most voters will take it. Still, the fact that one-third to two-fifths of voters endorse ideas such as election hacking, vaccine dangers, or government weather control shows that mistrust of institutions remains potent enough to sustain even unlikely claims among sizable minorities.

Together, the findings suggest that conspiracy belief in the U.S. is less about a taste for the bizarre and more about a mainstream, widespread erosion of confidence in institutions – a trend many have been highlighting in other contexts. The challenge is not simply fringe ideas at the margins, but the normalization of suspicion toward the very systems that shape political life, public health, and information.